How cleaner cookstoves are sparking an environmental and societal revolution

By Lisa Stiffler

Researchers say the Northwest is the perfect place for a cookstove revolution — and they’re already making progress toward that vision.

A collaboration between Vashon Island’s Burn Design Lab and the University of Washington’s Clean Cookstove Lab has resulted in the development of a more fuel-efficient, cleaner burning wood cookstove to be sold in Kenya and Tanzania beginning this fall.

Approximately 3 billion people worldwide — nearly half the world’s population — use open fires and simple stoves to cook and heat their homes, according to the World Health Organization. The stoves, which typically burn wood or charcoal, are responsible for a slew of devastating environmental and health problems.

The stoves spew pollution into poorly ventilated homes, leading to millions of deaths from pneumonia, stroke, heart disease and other illnesses. The demand for fuel results in massive amounts of logging — including roughly half the deforestation in Sub-Saharan Africa. And inefficient cookstoves are one of the largest sources of “black carbon,” a sooty pollutant that ranks as the second-largest manmade contributor to climate change.

“It’s a triple treat,” said Jonathan Posner, principal investigator of the UW’s Department of Energy-funded Clean Cookstove Lab. “You solve this problem, and you’re reducing the burden on the planet and the people who live on it.”

Burn Design Lab, located on an island west of Seattle, and the UW have developed what they’re calling the Kuniokoa stove — a natural-draft, wood cookstove that uses half as much fuel compared to the small, open-flame fires that many East Africans traditionally have used for cooking. The cookstove also reduces the amount of particulate air pollution by more than 70 percent.

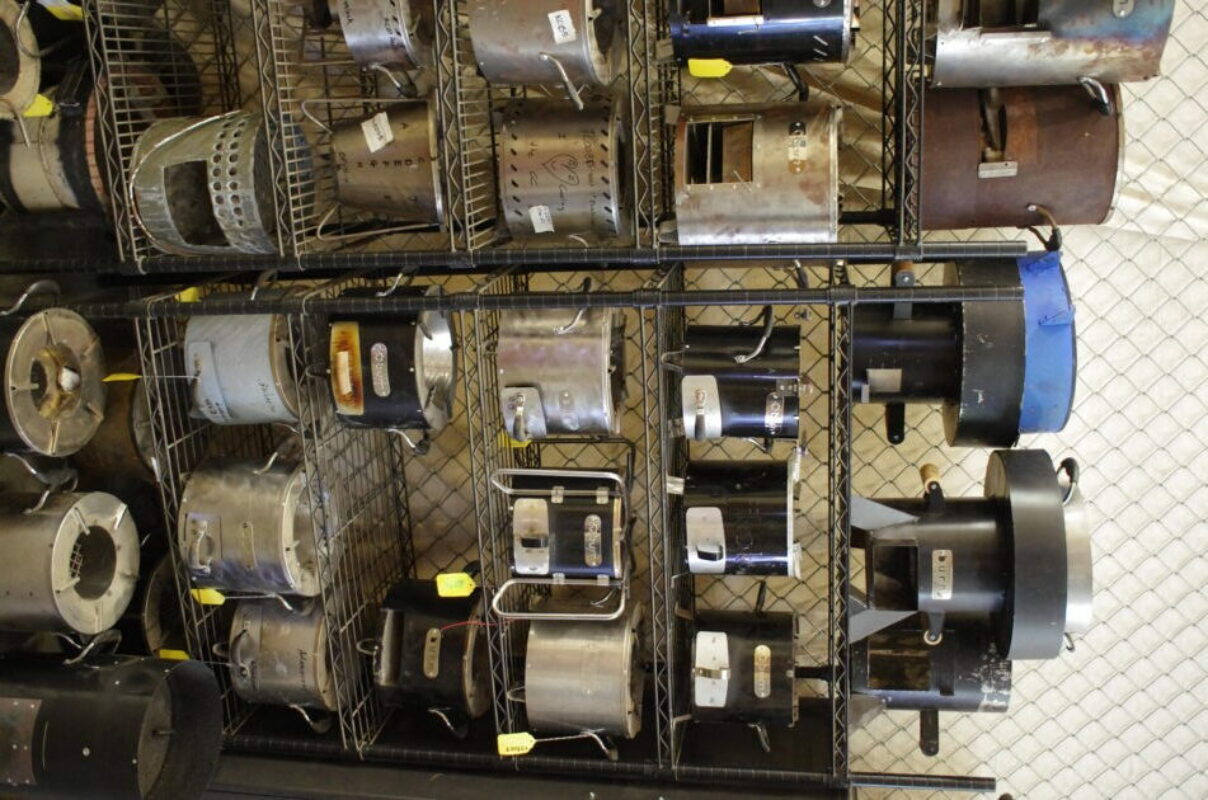

Paul Means, executive director of the nonprofit Burn Design Lab, said that people are often surprised that the stove technology is so difficult to work out.

They say, “haven’t people figured out how to make a cookstove?” Means said. The fact is, “it’s easy to make wood burn or charcoal burn, but we want it to be efficient and durable and fit the culture perfectly — and on top of that be so inexpensive some of the poorest people in the world can buy it.”

Historically there’s been relatively little investment into developing the technology, which requires engineering expertise in combustion, heat transfer and fluid dynamics.

“No one has really applied these rigorous scientific methods to this problem,” Posner said.

In addition to the Kuniokoa stove, the UW engineers have also a developed super-high performing wood cookstove, the “Formula One” version, as Posner calls it. The stove, which works without a chimney, is rated Tier 4 — the highest possible score on an internationally approved scale measuring fuel efficiency, pollution, indoor-emissions and safety.

“It’s as clean as a stove in your house,” he said. However, it’s not affordable or durable enough for mass production and sales in Africa, Posner said, but by building it, “we learn all the lessons of what makes a clean-burning stove, and then you apply it to something that is more practical.”

Funding for the cookstoves has come from multiple sources, including a $900,000 Department of Energy grant that got the UW lab off the ground and supported development work at Burn Design Lab. An additional $800,000 from Acumen and Unilever went to Burn Manufacturing Corp., the commercial side of the project, to help with production of the wood cookstoves. The stoves will initially be sold to workers on Unilver’s tea estates in East Africa.

The Kuniokoa stoves going on the market this fall have undergone extensive testing by people living in Kenya and focus groups there have ranked it well above competitors’ products. And they’re being built in Burn Manufacturing’s factory near Nairobi. More than half of the factory’s 100 employees are women.

“What Burn has done is really innovative, revolutionary,” said Peter Scott, CEO of Burn Manufacturing and founder of Burn Design Labs. “Nobody runs a modern manufacturing company [in Sub-Saharan Africa]. Nobody has penetrated the market the way we have.”

Inspired by his concern over Africa’s deforestation, Scott has been focused on building better cookstoves for more than two decades, working with a variety of organizations worldwide. He founded Burn six years ago, and since 2013 they’ve been selling a highly-efficient charcoal stove in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The charcoal stove, called the Jikokoa, is Tier 4 rated for five out of eight measures of performance and pollution. The company sells roughly 10,000 charcoal cookstoves a month in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo. (While wood is the fuel of choice in rural areas, nearly all urban households cook with charcoal.)

When Scott began working on cookstoves, he’d hoped to find an alternative fuel source — maybe solar or gas — to reduce the need for wood. But after realizing the technology wasn’t there, combined with the fact that people weren’t culturally ready to change sources, Scott threw his energy into making better charcoal and wood cookstoves.

He deliberately pursued a product that he could sell to residents of developing nations, rather than partner with an organization who would just give it away. Scott, and others involved with the project, believe it’s a smarter strategy to design something that people aspire to own to ensure they’ll use it and take care of it. They’ve sought to build something beautiful, functional and desirable.

“The world is littered with failed cookstove products,” Scott said. He didn’t want to join the rubbish pile.

Burn’s customers register their cookstoves and provide feedback on the product, which is expected to last two years. The charcoal stoves reportedly cut fuel use by 58 percent, which means that consumers recoup the cost of the $38 stove in about four months. Stove users also reported that they had half as many sick days.

On top of the wood-fueled cookstove coming out this fall, Burn is also launching another slightly smaller and less expensive version of the charcoal stove this winter.

The Burn factory has the capacity to could triple its stove output, Scott said. But while people want the cookstoves, it’s still difficult for many families to scrape together the money to buy them.

“That is the bottleneck,” Scott said. “The demand is very high.”

In addition to the cost challenges, which Burn continues working to address, supporters of the effort say they also need more large-scale research into the benefits of the clean stoves. Better data on their effects on health, fuel use and air pollution could attract more financial support.

“How do we get the data to show the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation that this is making peoples’ lives better?” asked Posner.

A recently published study on wood cookstoves used in India found few health and environmental benefits, but the stoves weren’t from Burn and there were problems getting people to adopt the devices.

“The major takeaway message is that we need rigorous field investigations,” said Ther Aung, a graduate student at the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability at the University of British Columbia. Aung was one of the authors of the research, which was published last month in the journal of Environmental Science and Technology.

“We need to do field-based evaluations at a community level so we can keep improving,” she said.

That’s where Posner’s vision for a Northwest-based clean cookstove institute comes in. He thinks this region is the perfect place for such an organization, given the local expertise in cookstoves, engineering, technology, epidemiology, global health and NGOs with a worldwide reach.

If you brought all the pieces together, he believes, the use of efficient cookstoves could take off.

“Half the world is cooking on open flames. Four million people are dying a year [from air pollution from the fires],” Posner said. “You have to fundamentally change how people are cooking.”