UW engineers to make cookstoves 10 times cleaner for the developing world

By Michelle Ma, UW News

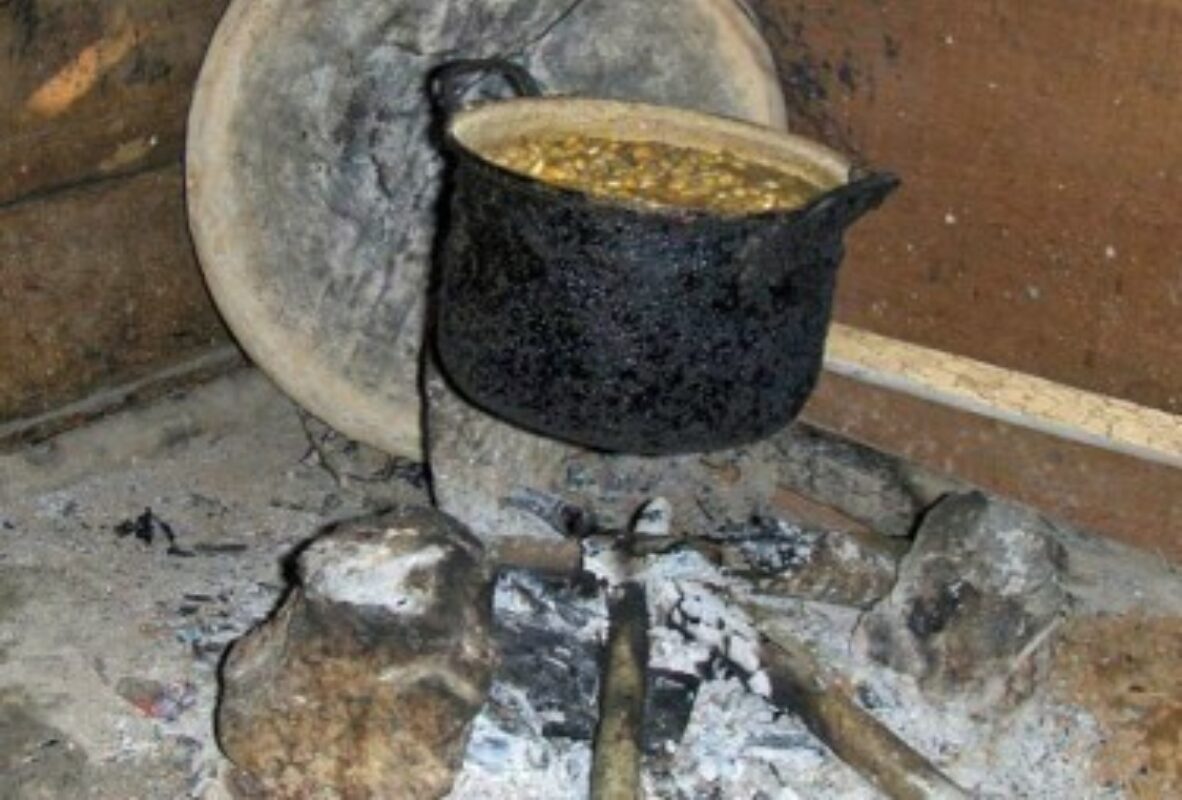

Nearly 500 million households – roughly 3 billion people, or 42 percent of the world’s population – rely on burning materials such as wood, animal dung or coal in stoves for cooking and heating their homes. Often these stoves are crudely designed, and poor ventilation and damp wood can create a smoky, hazardous indoor environment – day after day.

A recent study published in The Lancet estimates that 3.5 million people die each year as a result of indoor air pollution from open fires or rudimentary stoves in their homes. More than 900,000 people die from pneumonia alone, which has been linked to indoor air pollution.

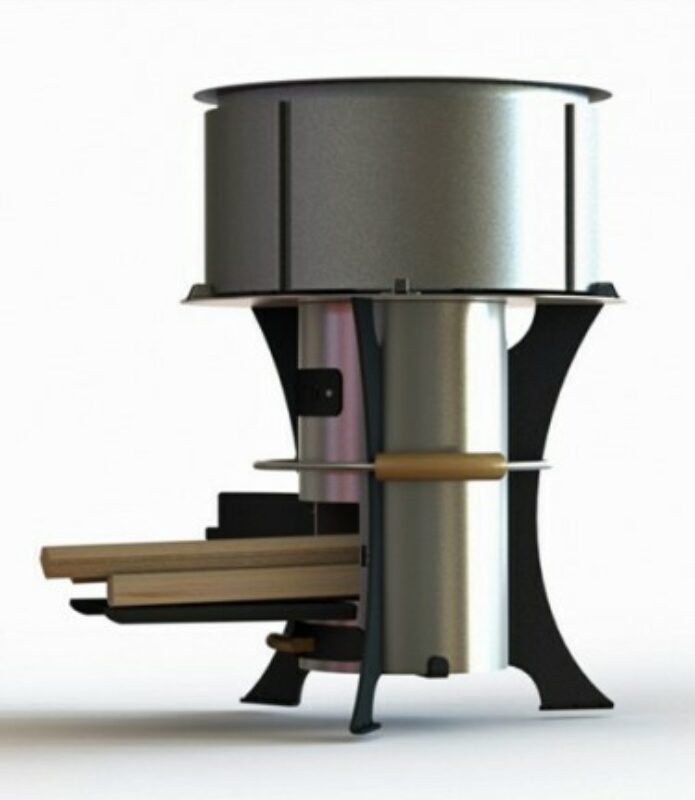

University of Washington engineers hope to make a dent in these numbers by designing a cookstove that meets a stringent set of emission and efficiency standards while still being affordable and attractive to families who cook over a flame each day. The team received a $900,000 grant in September from the U.S. Department of Energy to design a better cookstove, which researchers say will use half as much fuel and cut emissions by 90 percent.

“We are taking a holistic approach to designing a stove that will be clean and efficient, and also meet the needs of the people who are cooking,” said project lead Jonathan Posner, a UW associate professor of mechanical engineering. “Our goal of bringing cleaner wood-burning stoves to the developing-world market can only be met if we have an attractive product that meets key price and usability needs.”

The health risks and environmental impacts from solid-fuel cookstoves have only recently been studied and documented. In 2010 the United Nations Foundation, kick-started by then-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, launched the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves, a public-private partnership that is trying to get clean cookstoves and fuels to penetrate 100 million households by 2020.

In addition to creating an efficient stove, the UW researchers will also develop software that will allow other cookstove designers and manufacturers – especially those in the developing world – to test different elements as they make stoves to fit the needs of various communities around the world.

“The goal is not to just generate a design that is copied, but to provide a tool that allows others to design more efficiently on their own,” said John Kramlich, a UW professor of mechanical engineering who is leading the project’s combustion testing and modeling.

Modeling can be used to screen a large number of design ideas and find those that offer the highest payoff, Kramlich said.

Health factors aren’t the only issues with poorly designed cookstoves. Inefficient stoves also have environmental impacts, including contributing to deforestation and global warming through added particulates in the air. They also fuel gender inequality, Posner said, because it’s usually the women in each community who spend hours each day collecting wood and are exposed to smoke while cooking.

The UW-led team signed a contract with the Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy and plans to start the three-year project this fall. The team includes a variety of organizations with different specialties, including Burn Design Lab on Vashon Island, Wash., global health nonprofit PATH in Seattle, and Berkeley Air Monitoring Group in Berkeley, Calif.

At the UW, engineers will try to reduce smoke emissions and improve efficiency while designing a stove for East African communities that is inexpensive to manufacture. This will cut down on the amount of wood needed to cook and improve the air quality for families using the stove. The design likely will have simple parts and use natural drafts to move air through the stove, Kramlich said.

Perhaps most importantly, the stove must be familiar enough in design so people will want to use it, said Peter Scott, founder of Burn Design Lab.

“While there’s a place for high-tech stoves, for Africa and the developing world it’s important to have a robust design without a lot of moving parts,” Scott said. “Having this partnership will directly translate to a finished product in the market in three or four years.”

Designing cookstoves that are good for human health and the environment – and that take into account the social and economic needs of each community – is an interdisciplinary feat, Posner said. He hopes the UW can develop a research institute that brings in many departments and schools such as public health, sociology, law, business and medicine to tackle the problem.