BDL faces a new world with new leadership

Burn Design Lab faces a new world with new leadership

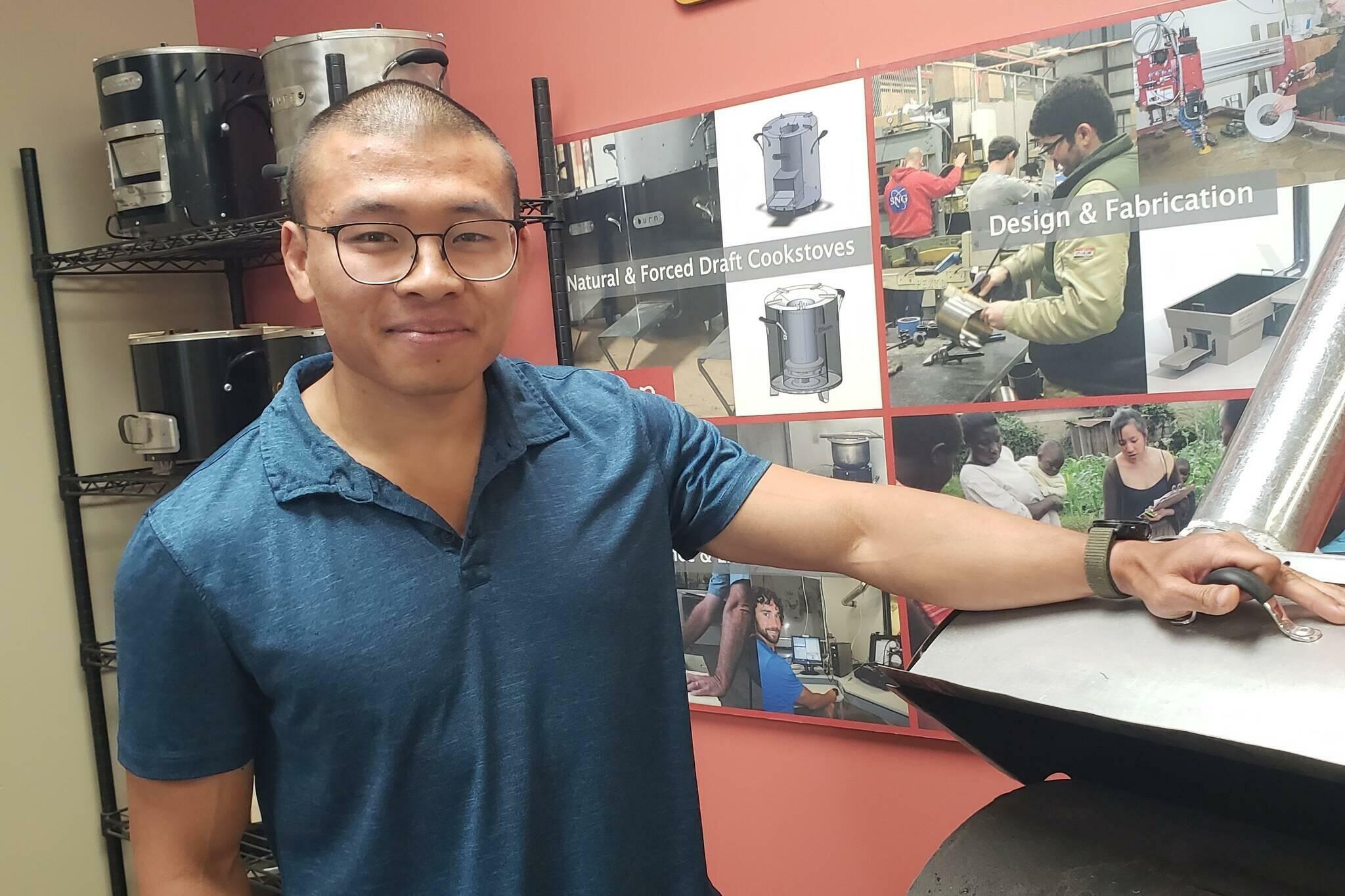

Jeremy Su arrived at Burn Design Lab in 2020 as an engineering student looking forward to a six-month internship to help address an alarming problem — the use of smoke-billowing stoves in Africa and elsewhere that harms the health of millions of women who spend hours cooking over them.

But Su never made it back to Northeastern University. Instead, he extended his internship by four months — he earned his degree remotely in part by taking one of his final exams in Ghana — and parlayed that into a permanent job.

Now, five years later, Su has just been named the new executive director at Burn Design Lab (BDL), a small, nimble and, by many accounts, effective organization on Vashon Island that works to design technologically appropriate stoves for developing countries.

At age 27, Su takes on the job at an auspicious, if challenging, time.

Though small, BDL has experienced remarkable success, helping to spark a revolution in cookstove technology and garnering international awards and acclaim along the way. It has designed nine stoves — clean-burning, durable and affordable — for a range of uses, from an industrial-sized shea nut roaster in Ghana to household stoves serving families in Kenya, Guatemala, Madagascar, Sierra Leone and elsewhere.

Those designs have been made into five million stoves manufactured in-country by partner organizations, saving over 9.5 million tons of wood and improving the health of more than 25 million people, according to BDL’s literature.

At the same time, BDL faces significant challenges. The Trump Administration’s efforts to dismantle the U.S. Agency for International Development have punched a hole in BDL’s forecasted income — three project grants BDL planned to apply for have been cancelled, including one to design a gasifier stove for use in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and another to scale up stove production in Sierra Leone. All told, BDL will have to raise about $250,000 to make up for the loss of those forecasted grants, a significant part of its $700,000 annual budget.

“These are tangible things that have been ripped away from us,” Su said. “Twenty to 30 percent of our revenue will be impacted by the lack of foreign aid. It’s big.”

BDL plans to turn to donors, including foundations and individuals, to make up the gap, and Su is optimistic the organization will be successful. But he noted that other small non-profit organizations doing excellent work in developing nations likely won’t make it. “We won’t have to close up shop. But we know other NGOs likely will.”

Paul Means, BDL’s former executive director and now vice president and senior advisor, said he’s saddened to see what’s happening in the world of international aid and development — an abdication, he believes, of the United States’ responsibility. USAID grants have made a huge difference in supporting innovation in the developing world, he said, enabling organizations like BDL to bring stoves from concept to commercial-scale production.

“There’s now a smaller pool of funds to support the work that we do. And it’s not just us. I think of the many organizations that are doing great work in all kinds of ways, like clean drinking water and human health,” he said. “It’s very sad, frankly.”

But Means says he sees a path forward for BDL; one foundation has already indicated it will increase its support. He also has confidence in Su. “Jeremy is a very remarkable young man. He’s very driven, and he’s results-oriented.”

BDL was founded 15 years ago by Peter Scott, a “rock star” of the cookstove world, according to a piece in the New Yorker magazine, who moved to Vashon after years of crisscrossing Africa in an effort to help communities develop more efficient stoves. Shortly after his arrival, he held a talk about the pain he experienced in Africa, where he saw widespread deforestation due to poor-burning stoves, and his vision for something bigger — an “army of engineers,” as he put it, who could scale up this work and and address what he saw as both a human health and ecological disaster.

Encouraged by a strong show of support on Vashon, Scott launched BDL as a nonprofit, with the help of several island volunteers, including Bob Powell, now a board member, and Ted Clabaugh, a retired attorney. They set up their lab in the Sheffield Building, attracted a rotation of enthusiastic engineering students to work as interns and began designing stoves — a laborious process of testing, tweaking, testing again and tweaking again. The number of prototypes, Su said, is countless.

In 2012, Scott founded a second company, Burn Manufacturing Co., a for-profit enterprise that could attract the capital needed to produce thousands of stoves. The company built a stove factory in Nairobi, Kenya, becoming the largest cookstove manufacturer in sub-Saharan Africa, and in 2016, Scott left Vashon for Kenya, where he now runs Burn Manufacturing full time.

Means, who was BDL’s research and testing manager under Scott, stepped up to become the executive director when Scott left, a position he held until January, when Su was named executive director. Under Means’ leadership, BDL became a completely independent entity — Burn Manufacturing makes some of its stoves, but there is no administrative or financial overlap. For most of his tenure, Means worked as executive director without drawing a salary in order to help BDL remain fiscally solid.

Now 70, Means says he plans to remain engaged. “I enjoy the work,” he said. “We all want to do something meaningful with our lives, to make a positive difference. This fits both of those things for me, as well as the opportunity to work with some wonderful people.”

Su, the director of engineering before becoming executive director, is equally passionate about the work. A hiker and backpacker, he uses the analogy of a campfire to illustrate the problems BDL is trying to address, as well as the stark difference between privilege and necessity.

“We make campfires for fun. But there’s always one person who has smoke in their face,” he said. “And that’s what two billion people face every day in other parts of the world. We do it for recreation. That’s not a given in many places.”

Su sat in his office at the Sheffield Building as he spoke, a room adorned with large photos — village scenes, women working over stoves, and more — that he took during some of his many trips to Africa. He pulled one off of a shelf and held it up — a photo of a handsome woman, her head wrapped in a colorful scarf, gazing directly at the camera.

This was from a visit to Ghana in 2022, he said, when he helped to install one of BDL’s first shea roasters at a locally run cooperative. The woman, Samata Iddrisu, was the cooperative’s organizer but had left after suffering some losses in her family — she was afraid to return, she told Su, because of the ill effects from shea roasting. But she decided to try again because of BDL’s vastly improved roaster, and during Su’s visit, she told him she’s glad she did. “It has already made me happier,” she told him.

That conversation took place at the end of Su’s three-month stint in Ghana, an important reminder of the importance of this work at a moment when he needed it, he said — he was feeling deeply exhausted from his grueling trip.

“At the end of the day, our ‘why’ is that we’re trying to improve women’s lives. That’s done through our cookstoves, but also through protecting forests. An intact forest also helps people’s lives,” he said. “That’s what we’re in business for. That’s how we define success.”

Su acknowledges that he has a hard road ahead of him. He’s worked as an engineer for the past five years, not as an administrator now facing a budget shortfall or as chief fundraiser for a small nonprofit.

But he’s confident BDL has the track record, relationships, staff and board to weather this next stretch. The organization will have to “double down and continue this work,” he said, being as strategic as possible. BDL’s leadership — including a board headed by Jonathan Posner, a University of Washington engineering professor in the schools of Mechanical Engineering, Chemical Engineering and Family Medicine — plans to hold a fundraising drive to try to fill the $250,000 revenue gap.

“I’m choosing to be hopeful,” Su said.

Posner, too, is confident, in part, he said, because of Su’s energy and enthusiasm. “Jeremy is the next generation,” he said. “He has Paul’s support and mentorship. But he also has new energy, and I can appreciate the power and magnitude of that. I’m tremendously optimistic.”

Leslie Brown is a former editor of The Beachcomber.